Johannesburg, 19 June 2024 – Webinar: Addressing Gauteng’s Impending Water Crisis:

19 June: 10:00 -12:00

Peter Varndell, representing the Strategic Water Partners Network (SWPN) as executive secretary, the host of the webinar, gave a welcome and introduced the panellists:

- Dr Sean Phillips, from the Department of Water and Sanitation, Director, General

- Ms Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze, Rand Water

- Nandha Govender, Eskom

Peter Varndell:

I just wanted to start with a little bit of background to this webinar, and why we have put this on. Many of you may be familiar with the Strategic Water Partners Network. It is a partnership between government, civil society and the private sector looking at the water supply/ demand gap affecting the country.

SWPN is a co-chair arrangement between the department (represented by DG) and private sector (currently represented by AB-Inbev).

SWPN has three core functions:

- Leadership and elevating action on water to an executive level: This includes, as part of a leadership function, communicating with the sector at large as well as to water users, and this fits in within that leadership bucket where we have the opportunity to learn from key players in the sector on challenges and solutions, both in our homes, but also in our careers to support improving the (water) situation.

- Partnerships: The second part relates to our partnerships, we work a lot on creating partnerships around specific issues. Two of our key drivers at this point in time relate to non-revenue water, leaks in municipalities and having actions in that space. The second is Gauteng what security. This aligns very well with topical issues that we are working on.

- Projects: And finally, we do projects together with, particular public sector partners and private sector partners to provide action and to reduce water demand. We have current projects in Polokwane and Nelson Mandela Bay and MOU’s with Rand Water and Johannesburg Water.

We are well aware that we are in a tricky situation in terms of the water supply supplying Gauteng as the economic heartland, its businesses as well as it’s over 13 million residents. It’s been a long time coming. But ultimately we have all realized that there’s a need to take action to stop these prolonged water outages that are starting to become a factor within the Gauteng landscape.

Today really is about hearing from the Department, from Rand Water and Eskom, a major water user. We will listen to their understanding of the issues, where we are, what the challenges are what the solutions are, and to try give guidance on what the steps forward will be and what we can all do.

The intent is really information sharing so that more people are aware of what the facts on the ground are. We will build on this in subsequent sessions to dig into more specific areas. For example, we may do one (webinar) with the municipalities on non-revenue water and water conservation, one on water financing, etc..

Address by Dr Sean Phillips (DG, DWS):

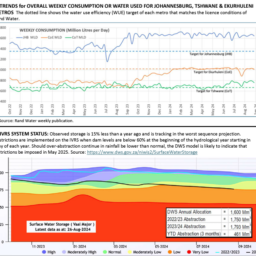

The key underlying problem in Gauteng is that there isn’t sufficient water in the Integrated Vaal River System, a system consisting of about 20 different dams, which provides water to Gauteng and to neighbouring provinces.

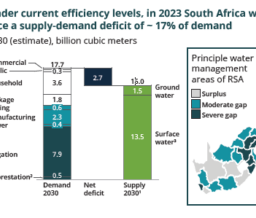

The main reason why there isn’t enough water in the Integrated Vaal River System is not because of a drought. It is because, there has been increasing demand, particularly in the Gauteng municipalities due to rapid population growth. Further, increased leaks in municipal distribution systems have also contributed to that increased demand.

As the National Department responsible for water resource planning we did anticipate that there would be this increase in demand for water in Gauteng and we planned the second phase of the Lesotho Highlands water project.

That project was originally planned to start a lot earlier than it actually started, and to come on stream by 2019, and to provide a huge amount of additional water into the Integrated Vaal River system. Unfortunately partly due to challenges in my department, many changes in leadership (at both ministerial and accounting officer level) over about a 10 year period has resulted in the start of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project being delayed by 9 or 10 years. Construction finally got going in 2022. Full scale construction in Lesotho is now underway. It’s a massive project. We’re trying to accelerate it as fast as possible, but realistically, it’s not going to be finished before 2028 and start providing that additional water into the Integrated Vaal River System.

As the National Department (DWS) we put an abstraction limits on any user, including agricultural users and Rand water, which extract water from the Integrated Vaal River System. And we do that using quite sophisticated hydrological models in order to ensure that the system remains sustainable and to ensure that even in the event of a severe drought the system will still have enough water to ensure at least a minimum amount of water to provide drinking potable water to residents that are served by the Integrated Vaal river System.

Rand Water is already exceeding its abstraction limits. In fact Rand Water is abstracting the maximum amount of water that it can abstract. And it would be irresponsible for us to allow them to extract any more water, because if there were to be a severe drought which can happen quite quickly it could mean that we could enter into a day zero situation in Gauteng. The abstraction limit prevents that from happening. The abstraction limit ensures that such a situation doesn’t arise.

Rand Water is abstracting the maximum amount of water that it can abstract. Rand Water is treating that water. It is fairly efficient at this, and doing that it has much lower water losses than the municipalities. Its losses are in the region of 3 to 4%. As you know, Rand Water then provides that water to the municipalities. Rand Water is planning a large scale construction program to develop additional treatment capacity, to be able to treat more water once there is more water in the Integrated Vaal River System. This can be achieved once we can raise the abstraction limit once Lesotho Highland Water Project Phase 2 starts providing more (new) water into the system.

At the moment, though we’re now in a situation where the demand for treated water in Gauteng is already occasionally exceeding the supply, particularly during peaks of demand such as when there are heat waves in Gauteng.

That very tight supply demand situation results in the problems that we’re experiencing where it can take weeks for water supply to be restored following a disruption. What happens when there’s a disruption such as due to an electrical or mechanical breakdown, or as what has happened during the last couple of years due to long periods of load shedding. What happens then is that the water levels in the reservoirs of the municipalities become depleted. When the mechanical or electrical repairs are completed, or when the load shedding comes to a halt, the very high demand comes back and because of the limited supplies from Rand Water it takes a very long time for the reservoirs to fill. The water is drawn out of the reservoirs just as quickly as it can be put in.

And that is the key reason why, sometimes people in some areas of Gauteng have been waiting for weeks to have their water supply restored following a disruption. If we didn’t have this very tight supply demand situation the situation would be much easier for the municipalities to fill their reservoirs quickly, and we wouldn’t have these long periods of time where people aren’t having any water following disruptions. Disruptions will always occur in municipal systems, there will always be mechanical and electrical breakdowns. But it’s because of the really tight supply and demand situation, and that these breakdowns are having such bad effects in terms of the duration in which people have to do without water.

There are some other contributing factors. As we know, the municipalities over a long period of time have neglected the maintenance of their infrastructure. And the relatively high level of breakdowns is due to that lack of maintenance. The municipalities also neglected making an investment in their infrastructure, as the demand has been growing.

On a more positive note many of the municipalities have since this situation developed over the last couple of years have substantially increased their budgets for investment in water and sanitation. Water infrastructure in particular. So, for example, Johannesburg Water has quite a substantial capital works program which it is currently implementing which involves doing things like building additional reservoir capacity and additional pumping stations, hence to make this system more resilient, in this very tight supply and demand situation.

The things that need to be done to minimize the risk of water supply disruptions over the next few years is the following:

- Firstly, we need to make sure that the Lesotho Highlands phase 2 project is implemented expeditiously, and is completed as soon as possible.

- The second thing that we need to do is focus is work with municipalities to get them to reduce the leaks in their distribution systems.

- The third thing that we need to do is to encourage the municipalities to do the kind of work that the city of Johannesburg is doing to improve performance of their systems and to invest in their infrastructure to make their systems more resilient

- The next thing that we need to do is generally try and reduce demand for water in Gauteng. Even if the municipalities are able to reduce leaks to improve the performance of their systems, to implement better measures such as pressure management in order to reduce their water losses will on its own not be enough to minimize the risk of water supply disruptions. We also need to reduce demand as measured by the average consumption per capita of the residents in Gauteng.

The average consumption per capita in Gauteng is high compared to international standards. It’s around 250 litres per capita per day, whereas the international average is around 170 litters per capita per day. Those figures include leaks, but even if you take leaks out of the equation, the average consumption per capita per day in Gauteng is still substantially higher than the international average. This is an anomaly given that Gauteng is a water scarce province.

So we need to do all of these things. If we’re going to be able to minimize the risk of water supply disruptions in Gauteng. If we don’t do all of them, if we only do 2 out of the 4 or 5 things, then we’re still going to have a high risk of disruptions. And what’s very important is for us to get the message across to all the residents of Gauteng and that all of these things that needs to be done need to be done.

We need to try and build trust and address the trust deficit and move away from the current situation, where, particularly in the media, it tends to be a blame game, and that whenever the water supply disruptions occur, there’s a search for who’s to blame. When we try and put this message across that the residents also need to play a part, and use water sparingly. Then, the blame game goes as far as indicating that now government is saying the residents themselves are to blame.

So we need to try and move, move away from this situation where it’s just about finding someone to blame and we need to all accept responsibility and accept that everybody has a role to play to minimize the risk of water supply disruptions including the national governments, the municipalities and the residents themselves.

We are starting a process facilitated by the World Bank, in which the SWPN is also assisting and participating. The private sector and civil society is collaborating to see if we can reach consensus on the problems and their causes, and what needs to be done about them, and then to see if we can have a jointly implemented initiative. A large scale awareness campaign is envisioned drawing on the lessons from Cape Town which was able to sustainably reduce the average consumption per capita per day when they were trying to avoid a day zero.

That is the element which is currently missing in Gauteng. The municipalities are trying to reduce their leaks. They could do more. They’re investing in their infrastructure. We are trying to accelerate Lesotho Highlands Water Project Phase 2. But the part that’s missing currently is the awareness campaign similar to that which is in Cape Town to bring down the average consumption per day.

Thank you, Peter.

Peter Varndell thanked the DG for his contribution stating that his address provided great context and key takeaways.

Question: What is the date of first delivery from Lesotho Highlands Phase 2 (Q2)

Peter further asked a clarifying question on when the first water from phase 2 of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project would be delivered. The DG confirmed that according to the current schedule the first water delivery would be in 2028.

Peter remarked that this implied that the situation until then would be one where we need to very carefully manage the available resources.

Question: What is the implications of the tunnel maintenance shutdown plan for this year? (Q11)

Peter Varndell requested information from the DG on the planned shutdown of the Lesotho Highlands transfer tunnel and the potential supply risks.

DG Sean Phillips response:

The tunnel maintenance is planned maintenance. It’s something which should be done. As you know, we have problems in South Africa, where, with a lack of maintenance and deteriorating infrastructure due to a lack of maintenance. The fact that we are doing planned maintenance on the tunnel, which is part of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project infrastructure should be looked on positively that we’re not neglecting the maintenance. The planned tunnel maintenance won’t have any impact on the water supply in Gauteng. Rand Water will still be abstracting during the maintenance period, so it’s not going to be a contributing factor to water supply disruptions in Gauteng.

Where the water supply might be somewhat affected, is water supply to irrigators and some of the small towns in the Free State, and we are engaging with those communities. And contingency plans have been put in place, including making sure that other dams which supply those areas are full of water before the maintenance starts.

Address by Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze (Rand Water)

Thank you, Peter, and good morning to everyone. Yes, the DG indicated that the main challenge is water scarcity in South Africa. As it stands now, Rand Water is over abstracting above the 1600 million cubic meters per annum limit. And mainly this is due to the fact that there is growing demand from the municipal sector. And again, there are existing consumer inefficiencies and new developments are coming, and there are also increased informal settlements that are coming up as well. This, then, means that the demand keeps on increasing. Over and above that the DG has indicated that we’ve got a serious challenge on increasing non-revenue water and water losses, particularly in the municipal sector.

We are losing more than 40% of our water that we are distributing to our customers. Moreover, the high water use inefficiencies in the municipal sector does not assist in exaggerating the challenge of water demand. It is then important that more emphasis be put specifically in the municipal sector to try and reduce the water as well as the water losses.

And more emphasis is needed to be placed in consumer behaviour. We need to embark on more awareness campaigns in an attempt to reduce the water demand in Gauteng, because we can do as much as we can but if the consumer behaviour is not changing that is not going to assist the situation.

So now, as it stands in light of the fact that the challenge of non-revenue water and water losses is increasing year in, year out, Rand Water is attempting to partner with municipalities in implementing water conservation and water demand management projects that would assist in reducing the losses as well as the non-revenue water, to ensure that the sustainability of water supply in Gauteng is secured.

Peter Varndell thanked Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze for her address. He acknowledged the consistent messaging about the challenge, particularly in the Gauteng situation with the abstraction limits, with the high level of water losses, and again, the need for a comprehensive approach that includes both government at a municipal infrastructure point of view, but as well as consumers at an industrial and at a domestic level.

Peter Varndell asked Nandha Govender to speak to the water risks and the impact these have on Eskom’s business.

Address by Nandha Govender (Eskom):

From an Eskom perspective besides just being a major user industrial water user I think it’s the importance of having water for our electricity production and generation and also the need for long term planning. So when you build a power station you have to look at the water supply. You have to look at a long term view. And so the nature of our business to make sure that water security is at the centre of that, and that talks to everything from the resource to the infrastructure. So we are part of a system, the Integrated Vaal River System.

As a strategic water user we do have certain benefits, in terms of curtailments or restrictions we are the last to be curtailed because of the need of water for electricity generation. We are part of a system and we cannot act as if we are not impacted. Some of the risk that the DG has alluded to is having an impact in terms of water demand from the same resource from where we are abstracting water from.

So we all have to play our part, we all have a role to play. And we have to look at it from a risk management perspective. So everything that we can do, whether it’s not only the municipalities, but all sectors, you know, coming together and playing their part in terms of water efficiency, reducing demand and also playing a part in terms of active involvement in terms of managing risk. I think that’s the kind of setting in terms of where we are at.

I think over the years we have always identified water security as a major risk to our business. And if you look at the evolution of Eskom you will see that our water footprint has reduced significantly the whole intent behind that was to become more water resilient, and also to make sure that water is not a major risk to our business.

Everything, from the choice of technologies to the introduction of dry cooling to the water use efficiency targets that we set for our power stations, to the water management, to our practices around reuse recycling is all part of an effort to reduce our water demand and make sure that for every kilowatt hour of electricity we generate the water component thereof is actually minimized.

That has been our recipe for success. We are part of a system, we see the risk. So that also calls for us to be active in the management of looking beyond just our own operations, being active in the space of working with our suppliers like the Department of Water and Sanitation and Rand Water to understand their challenges and work together with them, to make sure that we have water flowing to the power stations. Things like asset management, maintenance making sure that (maintenance) outages are happening, making sure the plant is available, etc, is part and parcel of our day to day jobs.

But I think more importantly is to make sure that our business continuity plans are in place. What could trip us up besides the demand supply gap? It could be any disasters like floods, etc. What are those things that going to come that’s going to be impacting on us? And how do we manage that proactively and not getting to a crisis situation like we are at the moment.

I think we have to look long term and see what’s coming at us. And I think the advantage of Eskom is that we’ve been through this with the load shedding sagas. There’s a lot of lessons to be shared with the rest of the other sectors in terms of what can be done in terms of best practice and how we turn the tide around that.

Water conservation and water demand management for me is a non-negotiable in every sector, every business, every household should be driving this. And I think it should be a national program that we embed this, not as a behaviour change, but also in terms of how we run our business from a sustainability perspective.

Peter, let me leave it at that.

Peter Varndell thanked Nandha for his contribution and further remarked on Eskom’s potential leadership role in learning from the energy crisis. Peter Varndell acknowledged that a lot of similarities arise out of the speakers but further remarked that there were some very fundamental differences in the water sector versus what played out in the electricity sector.

Peter Varndell:

You can’t put up a solar panel and generate water. On the energy side people were able to protect themselves and de-risk in many ways if they had the means. But water is very different in this context.

So it’s very much a collective response that addresses what we are able to move in the system. But again, I think some great learnings that we could take from incentives to businesses to improved energy efficiency and to some of the projects and private sector investments. There’s a lot that we can take from that, and perhaps that’s a discussion in its own right. But again, I think the key takeaway comes back to the same point that both the DG and Rand Water have shared with us, and that’s the situation that we are now in. It is absolutely critical that we drive water, conservation and water demand management. Both through the distribution infrastructure, but as well as at a consumer level.

Question: What are the financial investments required (Q4)

Do you have a view of what the investment requirements are, or the financial requirements are and where they may come from and where the gaps may be?

DG Sean Phillips response:

The water value chain has various elements to it. In a nutshell DWS provides raw water from schemes such as the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. We sell that water to various customers, including Eskom but also to the water boards like Rand Water who treat the water, and then sells it to municipalities, who distribute it.

We are raising the money for the Lesotho Highlands Phase 2, which is in the order of 40 billion rand completely from the markets through our entity called the TCTA. So it’s all private sector financing for the Lesotho Highlands Phase 2.

Rand Water has a planned capital growth program of approximately 30 billion rands in order for it to have the additional treatment and storage capacity required so that it can treat a lot more water once the Lesotho Highlands Phase 2 comes online.

Rand Water also borrows all its money for its capital requirements on the market. So again, it’s private sector finance. So if you add our (DWS) 40 billion plus Rand Water’s 30 billion, that’s 70 billion Rand, which is currently underway and due to be completed by 2028, to enable more water to be supplied to Gauteng, which is very substantial, and none of that has to come from the fiscus. It’s all borrowed money, borrowed from the private sector, largely from the banks and from the pension funds.

Now, of course, those loans need to be financed, and they need to be paid off and the money for financing and paying off those loans has to come from people paying their water bills and companies paying their water bills.

So we sell water to Rand Water who must pay us, and we use that money to pay off our loans. Rand Water, sells water to the municipalities, and it uses that money to pay off its loans. So the municipalities must pay Rand Water for the water provided to them, and in order to do that, the municipalities must have very efficient and effective revenue collection systems, and they must reduce their non-revenue water.

Municipalities aren’t going to be able to pay Rand water if they’re throwing away 30 or 40% of the water that they buy from Rand Water through leeks or if their billing and revenue collection systems are inefficient. So they’re not connecting as much as possible of the revenue that should be collected from their distribution of that water.

And that emphasizes Peter what you said at the beginning of this webinar of the importance of reducing non-revenue water at municipal level. The whole system depends on us successfully reducing non-revenue water at a municipal level because the financial sustainability right through the value chain is currently being threatened by the increasing non-revenue water at a municipal level.

Peter Varndell invited Salome to provide a Rand Water perspective specifically in relation to Project 1600, the gaps in funding required to close the municipal non-revenue gap and vision to support the municipalities.

Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze:

Yes, we do. What Rand Water is currently doing is to increase the tariff by 1% which would then be used to implement water conservation and water demand management projects in the Rand Water area of supply. So that is one project that is anticipated to begin in the next financial year.

So in terms of Project 1600, it is mainly aimed at ensuring that communications with all relevant stakeholders occur. The aim is to ensure that municipalities are using their water sparingly so that non-revenue water can be curbed.

Over and above that there are a lot of interventions that Rand Water is doing from a technical perspective. It has its own infrastructure development plan where in it has a lot of projects that are aimed at ensuring that the non-revenue water as well as the losses, are curtailed to meet the increasing water demand in Gauteng.

Peter Varndell:

I know there was a question around tariffs and the likelihood of increase in tariffs. The tariff that you’re referring to is the tariff that you charge the municipalities versus the bulk users. Do you (Rand Water) have a view on whether that’s going to be pushed onto the consumers, and whether the municipalities would be looking to increase tariffs. So that’s an unfair question for you, and we should have a subsequent discussion with the municipalities.

I’m not personally aware of how the pricing strategies work, so I don’t know if yourself or Dr Phillips would be able to comment on that.

Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze:

Yes, from a Rand Water perspective we are charging the municipalities, and then the municipalities will obviously charge that to the consumers. So that is one project that has not yet started, though it is going to start in the next financial year.

Peter Varndell:

Thank you. And Dr Philips is there anything you would want to venture on the tariff inside, are you expecting any changes to tariffs?

Sean Phillips:

Lesotho Highlands Phase 2 is going to have an impact on tariffs. You heard the figures that I gave that borrowing has to be funded and again it brings us back to the issue that we’re living in a water scarce country. The Lesotho Highlands phase 2 is a very, very expensive project. South Africa has limited remaining opportunities for capturing surface water. There aren’t limitless opportunities for capturing surface water. And the remaining opportunities are becoming increasingly expensive.

Over the last 100 years or so the engineers chose the most cost effective and cheaper options for building dams initially, and all those options have now been utilized, and any additional national water infrastructure that is constructed is focused on the remaining opportunities which tend to be the more expensive ones. Because water is scarce in South Africa, and continuing to provide high levels of increasing amounts of water is going to become increasingly expensive and that in itself has to be a driver of us using water more sparingly.

Peter Varndell

Thank you DG. I think you know the intention of these sessions is to provide clarity on these, so to the extent that we aren’t able to fully thrash out a particular topic please do feel free to reach out to us, and we can perhaps, at a future session cover very specific topics, so we can dig into them a little bit deeper.

Nandha, just coming back to yourself. You know it keeps coming back to water conservation and water demand management. From your experience at Eskom, and as well as within the water partners, what are the best levers to promote better water stewardship at a corporate level and a domestic level? Perhaps you can provide some guidance on that for us?

Nandha Govender:

I think you know you mentioned stewardship. So I think stewardship talks about bringing in expert specialists from all sectors working together. The problem is a bit more complex. Sometimes it’s not as it’s not just a technical problem, sometimes is a bit more to it. So I think the collective wisdom of bringing people together is very important. So I think that’s where the stewardship concept comes from.

And then, I think, also, looking at lessons learned within Eskom I think we’ve been a long partner with the department water and sanitation. I remember way back, we had a water conservation water demand management program MOU signed. And we’re re-initiating that given what’s happening in the Integrated Vaal River System.

And it’s all about committing to certain targets, committing to implementing best practices within your sites, and also promoting the importance of water and awareness around it. If everyone plays their part, then you’ll find that we may have some leeway in terms of that supply demand gap.

Hence I am also in support of what the DG is saying, we all have a role to play, and I think if you look at loadshedding, Eskom did make a plea to customers. With the support of the customers and consumers you start to see that you start to turn the tide like we are at the moment with 80 plus days without low shedding. So that’s good news. It has benefits all round, especially from water security supply perspective. It just alleviates the pressure.

So I think specific interventions, commitments, maybe MOU’s, putting money where your mouth is like funding the SWPN. Bring in the private sector, bring in your change champions, leaders to all come on board similar to what we did on the energy side, is to drive this as a collective, so everyone should be speaking from the same hymn sheet. Not just the Minister, and not just the DG, everybody.

Peter Varndell:

The Strategic Water Partners Network is established to work with the Department and our Municipalities and our water utilities to leverage our relationships with business and civil society, to do what we can to support this.

Our experience in the Gauteng water crisis discussion so far is that there is certainly alignment from all the government sector stakeholders as well as business and civil society players. And you mentioned earlier that the World Bank has been facilitating a process to align with everyone. And I guess, just from an independent point of view, I just like to acknowledge that that work has been going on as recently as yesterday (18 June 2024), having, discussions around the leadership group and the structures and what needs to be done. So really, just to acknowledge that is happening. We are all still trying to figure out exactly what roles and what functions belong to who and how we can best support.

But I think it’ll become more clear in the short term. And again, just to reiterate that there is an acknowledgement by all parties, be it the department, be it Rand Water, be it the municipalities, that there is an issue that needs to be dealt with, and it’s going to take a sum of all of the parts to resolve it.

Sean Phillips:

In the short term the most important one is to implement a communications and awareness campaign in Gauteng of a similar scale to that which was implemented in Cape Town. I’m sure quite a few of the participants in the webinar would have visited Cape Town during the time when Cape Town was approaching day zero, and would be aware that immediately when you entered Cape Town the message is about the need to use water sparingly.

And then the message is about the need for everyone to play a part. It was very successful, and that every individual household and every business had to play. So individual households can save some water, and that water saved by an individual household doesn’t make a lot of difference in the bigger scheme of things. But if most households in Cape Town displayed the same behaviour, then it did make a huge difference.

And they also did clever things like they made publicly available information even down to a household level about the extent of water usage in individual households, so that they introduced a degree of peer group pressure, so that people could see in their communities which are the households which are using high amounts of water, and therefore taking the whole of Cape Town closer to a situation of day zero. It was extremely effective.

Even to this day Cape Town still has the lowest average consumption of water per capita per day of all the cities in South Africa, because that water conservation and demand management program and awareness campaign had a sustained impact on water usage in Cape Town. So our immediate priority is to work with the private sector in South Africa and organized business nationally with prominent civil society people and with sector experts to try and develop these messages to develop an awareness campaign for Gauteng.

And the first part of it is to reach consensus as to what are the key issues? At the moment there’s a very low level of trust on anything government has to say. We need to address that trust deficit, so that when we ask people to use water more sparingly we don’t get a response that now you’re blaming the residents for your own poor maintenance of the water infrastructure and your own inability to deliver water so we need to build up trust that government is trying to improve what it’s doing, what is has to do it on its side. But residents also need to play a part. That’s our immediate, most important objective.

Peter Varndell:

I think, what drives a lot of this is not saying that infrastructure doesn’t need repair. It’s just a phasing approach. You can make immediate impacts and behaviour whilst in the more medium term, you raise finance to sort out some of the more critical issues.

And I know a lot of our partners and discussions point to the importance of reliable factual data, transparency around that data, so that everybody has a clear view of what the situation is. So again, just to reiterate that’s been acknowledged by all stakeholders as an important piece.

But then, importantly, the communication of that and what it means, and what it means to all of us, and what we can do at a business level and a personal level is important. So this is really just a first start of all of that. Just to point that the Strategic Water Partners Network are represented in that structure. So if there are any partners that want to do more in supporting the water situation please do get hold of myself or Michelle Proude, maybe you can just put your contacts on in the chat. Do feel free to get hold of us. We’re happy to guide.

We have a very specific approach from the Strategic Water Partners Network from a convening point of view to try and aggregate interest and intent into projects that can make a difference. We are seeing a lot of interest from businesses at this point in time in managing operational business risk by doing water demand projects in their direct zones that have an impact on water storage and obviously has an impact in on their own operational water supply. We have seen interest from companies that have global ESG reporting requirements to be water neutral in their operations. So again, there are projects that we can pick up and structure for partners to effectively implement water demand reduction and water security projects. And then also a lot of the projects are in communities. So there is a strong community project level initiatives like local plumbing, local household plumbing type projects.

The strong interest would be to link that to potential CSI opportunities from businesses. So there’s a lot of different opportunities and different means to participate. I’m happy to give guidance to any companies that may want to dig a little bit deeper into this.

Question on water supply gap (Q34)

A question was asked on the supply or demand gap, especially in high demand times? From another angle how much should the projected demand be reduced to at least sufficiently reduce the impending risk?

Sean Phillips:

The demand fluctuates daily and seasonally, and is influenced by factors such as heat waves. Our estimate is that if we can reduce demand by about 8%, then we should be able to minimize the risk of supply disruptions caused by demand exceeding supply.

Given that loans need to be repaid is there any motivation from DWS, is a municipal perspective for large industrial water users to affect their own water recovery? (Q28)

Sean Phillips:

We don’t have any specific incentives for large water users to get their own supply. But, on the other hand, they also aren’t any major hurdles to them doing so currently. This is different to the electricity sector. You will recall that there used to be some regulatory hurdles preventing the private sector from generating its own electricity, which have been removed.

So we’re not in that situation in the water sector where we have such regulatory hurdles. We do have a requirement which is in the National Water Act that any water user which draws raw water and uses it needs to get a water use license. And I think that needs to remain because we need to take care of our scarce water resources and make sure that they use water in a sustainable way. But we have been implementing and continue to implement measures to make sure that those water use license application processes are implemented efficiently and that they don’t cause an undue delay to water users doing that.

I think, for some of the major water users like Eskom, for example, or Sasol, which buy water from us directly it will be difficult for them to meet their huge water needs through developing their own supply. At the moment in Gauteng the key problem is that there is a shortage of treated water.

So that one of the key things is for us to encourage users of that treated water that they both use water more efficiently but also to develop their own supply. Part of the awareness campaign will be to encourage residents, for example, to install rainwater harvesting facilities, at their residences, which would reduce the demand for treated water.

Question: What is project 1600? (Q25)

Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze:

Project 1600 is the allocation that Rand Water have received from the Department of Water and Sanitation, hence the name Project 1600. Rand Water are entitled to abstract 1600 million cubic meters per annum from the Integrated Vaal river System.

Question: Is there work and support underway to support municipalities with existing challenges around billing and revenue collection? (Q23)

Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze:

The plan is to ensure that all the municipalities have got billing strategies in place to assist in enhancing such and to ensure that municipalities operate optimally, because when municipalities are failing, that means they won’t be able to pay us at Rand Water, and that creates a serious challenge for us. So yes, there is a plan of ensuring that billing strategies are in place.

Sean Phillips:

DWS provides intensive support to municipalities, and the metros in particular to improve their billing and revenue collection. We have put in place a water partnerships office in partnership with the DBSA to assist municipalities to put in place partnerships with the private sector, to reduce non-revenue water and an element of that could also include getting the private sector to assist the municipalities to improve their billing and revenue collection systems.

We’re encouraging municipalities to make use of this offer, and to put in place such partnerships with the private sector. It’s an anomaly that municipalities can say that they don’t have enough money to fix, for example, large water pipelines that are leaking when, if they did fix those water pipelines and reduce the leaks, then they would get more revenue.

It’s important to mobilize private sector finance so that the financing gap can be addressed and that private sector finance can be used to do things like fix the large broken plants which are leaking, and that finance can be paid off through increased revenue from the reduced leaks, or through reduced expenditure on buying water from Rand Water, which is then lost through leaks.

So that’s a major focus for us, to resolve that financing problem to reduce non-revenue water.

Peter Varndell:

And just to add on to that, just to note the Strategic Water Partners Network also plays a fringe role in this space. We supported Polokwane municipality on non-revenue water reduction. Both from physical projects to reduce and to come up with a non-revenue water strategy, then to execute some of the projects, to reduce water demand, but then also importantly, to do the the work required to understand how to raise the full value of non-revenue water finance required. And to the DG’s point, that has now been handed over to the Water Partnerships Office to structure something around performance based contracting that will start to make a major impact there.

But our aspirations from the water partners network is to leverage our partners. We already have had contributions from SAB and Anglo American into very specific municipal water partnerships which are effectively non-revenue water funds. And we’re looking to scale that in the in the event that we can match our work with the interest of business. We also know that business isn’t there to continually pay for fixing these issues. But there are certainly areas in which there is alignment of interest where these projects can be catalytic to the longer term play around the water partnerships office. So again, happy to share anything that they would like to hear on that front.

Question: What about underground water? Is there any plans in using underground water to increase water supply? (Q)

Sean Phillips:

Groundwater is largely a local issue in that for residents to put in boreholes to use a relatively small amount of groundwater doesn’t require a water use license from the department. So currently, it’s quite an unregulated environment for residents to put in place their own boreholes. It is something which we encourage, but it needs to be monitored to make sure that groundwater is used sustainably, and there isn’t over abstraction. We are encouraging Municipalities to encourage residents, or at least not to discourage residents, from contributing to addressing this problem by getting additional source of water, such as implementing boreholes, and such as rainwater harvesting.

There are also some municipalities in Gauteng which may be able to have larger ground water schemes. And we encourage them to plan for that, and to assess whether that’s viable and whether they have sufficient resources of groundwater to do that. The larger groundwater schemes would require water use license from that. But as long as the conditions are such that the groundwater levels would be sustained, we would normally approve such license applications. So yes, increasing use of groundwater in a sustainable way is part of the solution.

Question: What is Eskom’s view on the impact of load shedding or unplanned power outages on water security at the municipal level (Q)

I think it goes without saying that load shredding has had an impact in terms of pumping treatment and distribution of water supply. And I think this comes back to the planning and risk management. I think everybody has been taken off guard especially at the municipal water board level. So I think, apart from alternative power supplies which should be part and parcel of your business planning I think the alternative is in terms of making sure you have security of power supply. But I think your networks redundancy in terms of power supply as well but I think you need to plan for outages. Between Rand Water and the water boards and municipality, they need to cater for maintenance. The maintenance needs to happen like the DG is saying, maintenance is key.

So it’s a similar scenario at Eskom, where we had a problem of not doing our maintenance we have to create space for maintenance. And that’s in a way we had increased some of the levels of load sharing. But if you reduce the demand it then reduces the stages of load shedding similarly. I think from a water supply perspective, the extent of restrictions or curtailments will reduce. If capacity is created for maintenance, I think additional storage wasn’t part and parcel of the local distribution networks but now it is part and parcel of what is required.

You have to cater for water storage like we have to cater for energy storage. The advantage for Eskom we had the integrated renewable energy Independent Power producer program, which has now brought in about 11,000 megawatts into the grid. That has been quite substantial over the past 2 years.

I don’t know if there is a similar kind of thing on the water side. Where can you get water? But we all link to the same system. There’s no water that you can create apart from going back to the Integrated Vaal River System. I think that maybe the alternative is reuse and waste. How do we use that, and what applications utilize that? And what can we then do in terms of other applications. Maybe we need to look at water quality being the way of how we allocate different water qualities to different users. But our systems are designed as linear systems. They all go through the same pipeline. So it’s very difficult to be able to manage different water qualities going through similar pipelines.

Closing remarks by Sean Phillips:

So I want to thank everyone for participating. This is part of our process of trying to make government more transparent and accountable, and to try and build consensus and understanding of what are the problems and what’s being done about them, and to try and address this trust deficit which understandably exists.

Closing remarks by Salome Chiloane-Nwabueze, Rand Water:

Last thoughts from my side is that we all have to partake in terms of ensuring the security of water supply in Gauteng and in the country at large. It is not just the responsibility of water boards or municipalities, or the Department of Water and Sanitation.

We have indicated here that education and awareness is critical meaning that it becomes the responsibility of each and every individual in South Africa to ensure that water is conserved in order to enable sustainability of water supply in Gauteng and in South Africa at large. Thank you.

Closing remarks from Nandha Govender, Eskom:

What we need to recognise is that It’s not going to be a short term issue. Even if the Lesotho Highlands Phase 2 comes on stream, we already know that the demand is going to exceed the supply.

In the case of Eskom it took a while to turn the tide, similarly with improving the water supply situation it’s going to take us a while. But I think partnerships is key. Leadership is key. Collaboration is key. And I think we need to bring in the private sector from not only a financing / funding, but also from an innovation perspective. And like, I said, I think water conservation water demand management is something that we need to drive actively across all sectors.

Closing remarks from Peter Varndell:

Thank you to the team in the back end. And thank you to all of you for your time. I think if I can just leave with one parting thought as it’s been mentioned by the Department and by Rand Water that they are very open to sharing this information. They have never turned down an opportunity to support us in any of these types of sessions to discuss with partners. If we can help them to broaden this message, it’ll be very helpful. We have only had 150 people on this call today.

We will publish the recording and try to summarize the report for you all and put on the website, we’ll communicate that with you.

But if you can help to be advocates as well in talking to your own communities, whether it be at your own business level, talking to your employees, to your stakeholder groups that we can start to broaden this message. This is really just a starting point, we would hope in the future to get a lot more detailed on numbers, facts, interventions, etc. And again, if we have got a network of people that can help us to distribute the message we would be in a lot stronger position to be able to act together. We are fully aware that there is acknowledgement at all levels that there’s interventions to be done at a bulk level, at a distribution level and at a municipal level but also at an industrial and private level.

I think it’s important that we start to put numbers against that so we can start to see our own impacts can have an impact on our own wellbeing and good standard of living and strong business. So if you can help us with that I think it’ll be really much appreciated that we can start becoming an advocacy and a leadership group in our own right, with the information that we all have.

Everybody’s asking the questions around the dinner table, we hopefully will start to provide some of the facts around that that you can all share to demystify the situation at this point. So again, thank you very much, and thank you for always being available. We will communicate what future sessions will be coming up. Thank you

All the Best.

M Ginster, 21 June 2024

Note: The webinar has been transcribed and edited for clarity while maintaining the general flow of the dialogue.

For further information about this webinar or to be added to our database for future events, please contact the SWPN Secretariat at swpn.secretariat@thenbf.co.za.